Overview

Download the code on GitHub

A.R.M.O.R (Advanced Resilient Mode of Recognition) is a C# Framework designed to protect your ASP.NET web applications against CSRF attacks. This article explains how you can leverage ARMOR across an application built on MVC, Web API, or a combination of both. For more information on ARMOR or the Encrypted Token Pattern, please read this article.

The ARMOR WebFramework

The ARMOR WebFramework is a toolkit that provides boilerplate components intrinsic to ASP.NET, such as custom Authorization attributes, Filters and a range of tools to facilitate Header-parsing and other mechanisms necessary to secure your application. You can download the code here.

Securing Your Application with ARMOR

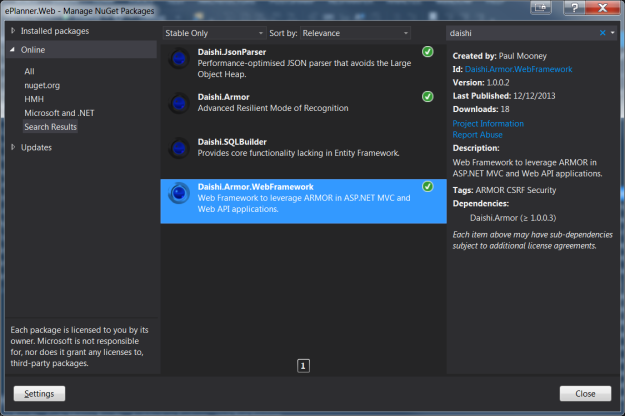

Download the Nuget package Daishi.Armor.WebFramework:

Once applied, you will have full access to the ARMOR API. Implementing the API is simple, as follows.

Add the appropriate Application Configuration settings

Add the following markup to your Application Configuration file:

<add key="IsArmed" value="true" /></b>

<add key="ArmorEncryptionKey" value="{Encryption Key}"/></b>

<add key="ArmorHashKey" value="{Hashing Key}"/></b>

<add key="ArmorTimeout" value="1200000"/></b>

The keys are as follows:

- IsArmed – Toggle feature to turn ARMOR on or off at an application-wide level

- ArmorEncryptionKey – The key that ARMOR will use to encrypt its Tokens

- ArmorHashKey – The key that ARMOR will use to generate a Token Hash

- ArmorTimeout – the time in milliseconds that ARMOR Tokens are valid for after generation

That’s it, we’re done with configuration. You can generate keys as follows using the RNGCryptServiceProvider class in .NET:

byte[] encryptionKey = new byte[32];

byte[] hashingKey = new byte[32];

using (var provider = new RNGCryptoServiceProvider()) {

provider.GetBytes(encryptionKey);

provider.GetBytes(hashingKey);

}

Both key values are 256 bits in length and are stored in the Application Configuration file in Base64-encoded format.

Hook the ARMOR Filter to your application

There are two main components to consider in the ARMOR WebFramework

- Authorization Filter – validates the incoming ARMOR Token

- Fortification Filter – refreshes and reissues a new ARMOR Token

The Authorization filter reads the ARMOR Token from the HttpRequest Header and validates it against the logged in user. You can authenticate the user in any fashion you like; ARMOR assumes that your user’s Claims are loaded into the current Thread at the point of validation.

Given that the MVC and Web API use different assemblies, the ARMOR Framework provides dual components that cater for both.

In terms of Authorization:

- MvcArmorAuthorizeAttribute

- WebApiArmorAuthorizeAttribute

- MvcArmorFortifyFilter

- WebApiArmorFortifyFilter

And Fortification:

- MvcArmorFortifyFilter

- WebApiArmorFortifyFilter

Generally speaking, it’s ideal that you refresh the incoming Token on every request, whether that request validates the Token or not; specifically GET requests. Otherwise, the Token may expire unless the user issues a POST, PUT, or DELETE request within the Token’s lifetime.

To do this, simple register the appropriate ARMOR Fortification mechanism in your application.

For MVC controllers:

public static void RegisterGlobalFilters(GlobalFilterCollection filters) {

filters.Add(new HandleErrorAttribute());

filters.Add(new HandleExceptionFilter("", "Error"));

filters.Add(new MvcArmorFortifyFilter());

}

As you can see, the MvcArmorFortifyFilter is now registered in MVC.

For Web API Controllers:

config.Filters.Add(new WebApiArmorFortifyFilter());

Add the above in the WebApiConfig.cs file.

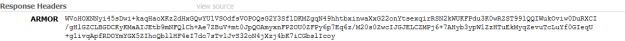

Now, each HttpResponse issued by your application will contain a custom ARMOR Header containing a new ARMOR Token for use with the next HttpRequest:

Decorate your POST, PUT and DELETE endpoints with ARMOR

In an MVC Controller simply decorate your endpoints as follows:

[MvcArmorAuthorize]

And in Web API Controllers:

[WebApiArmorAuthorize]

Integrate your application’s authentication mechanism

Your application presumably has a method of authentication. AMROR operates on the basis of Claims and provides default implementations of Claim-parsing components derived from the IdentityReader class in the following classes:

- MvcIdentityReader

- WebApiIdentityReader

Both classes return an enumerated list of Claim objects consisting of a UserId Claim. In the case of MVC, the Claim is derived from the ASP.NET intrinsic Identity.Name property, assuming that the user is already authenticated. In the case of Web API, it is assumed that you leverage an instance of ClaimsIdentity as your default IPrincipal object, and that user metadata is stored in Claims held within that ClaimsIdentity. As Such, the WebApiIdentityReader simply extracts the UserId Claim. Both UserId and Timestamp Claims are the only default Claims in an ArmorToken and are loaded upon creation.

If your application leverages a different authentication mechanism, you can simply derive from the default IdentityReader class with your own implementation and extract your logged in user’s metadata, injecting it into Claims necessary for ARMOR to manage. Here is the default Web API implementation. As you can see, the code is very straightforward:

public override bool TryRead(out IEnumerable<Claim> identity) {

var claims = new List<Claim>();

identity = claims;

var claimsIdentity = principal.Identity as ClaimsIdentity;

if (claimsIdentity == null) return false;

var subClaim = claimsIdentity.Claims.SingleOrDefault(c => c.Type.Equals("UserId"));

if (subClaim == null) return false;

claims.Add(subClaim);

return true;

}

ARMOR downcasts the intrinsic HTTP IPrincipal.Identity object as an instance of ClaimsIdentity and extracts the UserId Claim. Deriving from the IdentityReader base class allows you to implement your own mechanism to build Claims. It’s worth noting that you can store as many Claims as you like in an ARMOR Token, so feel free to do so. ARMOR will decrypt and deserialise your Claims so that they can be read on the return journey back to the server from the UI.

Adding the ARMOR UI Components

The ARMOR WebFramework contains a JavaScript file as follows:

var ajaxManager = ajaxManager || {

setHeader: function(armorToken) {

$.ajaxSetup({

beforeSend: function(xhr, settings) {

if (settings.type !== "GET") {

xhr.setRequestHeader("Authorization", "ARMOR " + armorToken);

}

}

});

}

};

The purpose of this code is to detect the HttpRequest type, and apply an ARMOR Authorization Header for POST, PUT and DELETE requests. You can leverage this on each page of your application (or in the default Layout page) as follows:

<script>

$(document).ready(function () {

ajaxManager.setHeader($("#armorToken").val());

});

$(document).ajaxSuccess(function (event, xhr, settings) {

var armorToken = xhr.getResponseHeader("ARMOR") || $("#armorToken").val();

ajaxManager.setHeader(armorToken);

});

</script>

As you can see, the UI contains a hidden field called “armorToken”. This field needs to be populated with an ArmorToken when the page is initially served. The following code in the ARMOR API itself facilitates this:

var nonceGenerator = new NonceGenerator(); nonceGenerator.Execute(); var encryptionKey = Convert.FromBase64String(ConfigurationManager.AppSettings["ArmorEncryptionKey"]); var hashingKey = Convert.FromBase64String(ConfigurationManager.AppSettings["ArmorHashKey"]); var armorToken = new ArmorToken(User.Identity.Name, "MyApp", nonceGenerator.Nonce); var armorTokenConstructor = new ArmorTokenConstructor(); var standardSecureArmorTokenBuilder = new StandardSecureArmorTokenBuilder(armorToken, encryptionKey, hashingKey); var generateSecureArmorToken = new GenerateSecureArmorToken(armorTokenConstructor, standardSecureArmorTokenBuilder); generateSecureArmorToken.Execute(); ViewBag.ArmorToken = generateSecureArmorToken.SecureArmorToken;

Here we generate the initial ARMOR Token to be served when the application loads. This Token will be leveraged by the first AJAX request and refreshed on each subsequent request. The Token is loaded into the ViewBag object and absorbed by the associated View:

<div><input id="armorToken" type="hidden" value=@ViewBag.ArmorToken /></div>

Now your AJAX requests are decorated with ARMOR Authorization attributes:

Summary

Now that you’ve implemented the ARMOR WebFramework, each POST, PUT and DELETE request will persist a Rijndael-encrypted and SHA256-hashed ARMOR Token, which is validated by the server before each POST, PUT, or DELETE request decorated with the appropriate attribute is handled, and refreshed after each request completes. The simple UI components attach new ARMOR Tokens to outgoing requests and read ARMOR Tokens on incoming responses. ARMOR is designed to work seamlessly with your current authentication mechanism to protect your application from CSRF attacks.

Connect with me: